When you can’t buy that Sony PS5 or Ford F-150 pickup, blame the chip shortage. A worldwide problem triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic has metastasized into a years-long disruption of everything electronic and is prompting governments to spend lavishly on chipmaking subsidies.

The shortage is leading the tech industry and politicians to try to reverse the United States’ waning importance in the microprocessor business. The US government isn’t happy with how reliant the country’s economy and military have become on Asian high-tech manufacturing. And chipmakers — salivating at government subsidies to underwrite research and new factories and forecasting a widespread increase in chip demand — are investing as never before.

The chip shortage is also shining a new spotlight on the state of US manufacturing and how much of it has moved out of the country. Intel, which has slipped to third place behind Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) and Samsung Foundry, hopes to take advantage of rising demand and government funding to reclaim its leadership position.

One huge change: In January, Intel said it’ll $20 billion on two chip fabrication plants, or fabs, near Columbus, Ohio. The new “megafab” site eventually could house eight Intel fabs costing $100 billion in total.

“We don’t want to create a situation where the United States, which created the semiconductor industry and Silicon Valley, would be completely dependent on other nations for that product,” said Al Thompson, who leads Intel’s US government relations.

The idea of “technological sovereignty” is loosening government purse strings. In the US, Congress is working on a bill that would provide chipmakers $52 billion. The House of Representatives passed its version in February after the Senate’s work on the bill in 2021. A few days later, the European Union proposed 15 billion euros ($17.1 billion) in new funding through a Chips for Europe initiative.

The chip industry’s new course is part of what some call the decoupling, which at least to some degree is pulling the Chinese and US economies apart. No one expects supply chains without links overseas, but the chip shortage response definitely has a nationalist flavor.

Asian manufacturers aren’t standing idle as Intel invests in capacity increases. In January, while reporting record revenue for the fourth quarter of 2021, TSMC said it will invest between $40 billion and $44 billion in new chipmaking plants and equipment in 2022 — an enormous amount.

“Foundry capacity will be precious for the foreseeable future as demand for semiconductors only grows,” said Creative Strategies analyst Ben Bajarin.

Here’s what’s going on and what’s at stake.

What started the chip shortage?

In short, the COVID-19 pandemic and a lot of shock waves that traversed the world’s economy. Demand for work-from-home technology like PCs, tablets and webcams soared beyond the semiconductor manufacturing industry’s ability to supply chips — not just the big CPU brains of a laptop but also the host of supporting chips required to produce things like dishwashers, baby monitors and LED light fixtures.

The chip shortage soon extended beyond remote work and school needs to home entertainment products like tablets, game consoles, TVs and graphics cards for gaming PCs, all of which people stuck at home were buying in record numbers. Compounding the problem: a fire at Japanese chipmaker Renesas Electronics, and crippling winter weather in Texas that knocked more than 70 power plants offline and cut juice to a Samsung chip plant.

COVID lockdowns led automakers to put chip orders on hold. Those companies rely disproportionately on cheaper processors that don’t require cutting-edge chipmaking technology. By the time they realized demand was picking up, chip plants had allocated their capacity to other customers.

And that wasn’t all. A glut of shipping and dearth of shipping containers has snarled delivery of not just finished goods but also their components and raw materials. Cars and computers require hundreds of electronic components, but just one missing component means a product can’t be sold. For an advanced processor, there’s likely only one company building it.

How long will the chip shortage last?

It probably won’t get any worse, but it’ll likely last for several more months. Chipmakers have worked to squeeze as much new capacity as they can out of their fabrication facilities, or “fabs,” but it takes years to build new fabs and ramp up production.

Intel Chief Executive Pat Gelsinger told CNET that he thinks we’re almost through the worst of the chip shortage, which will last through the second half of 2021. He predicts it’ll gradually ease through 2022 and fade in 2023.

Mismatches in chip supply and demand have been common for decades, but not like this. “We’ve always gone through cycles. This time it’s different,” AMD CEO Lisa Su said in September at the Code conference. She, too, expects this chip shortage will ease in 2022. But IBM CEO Arvind Krishna thinks it’s more likely the chip shortage will last through 2023 and even 2024.

What’s being affected by the chip shortage?

It’s easier to say what isn’t being affected. Just about anything with a power cord these days uses chips, so the shortage has hit cameras, microwave ovens, TVs, pacemakers, washing machines and more.

Worst hit is the auto industry. Cars are now studded with computer chips that control everything from infotainment systems to antilock brakes, and the car-making industry has relied heavily on “just-in-time” purchasing that cuts costs but means there’s no big inventory of parts to buffer against shortages. The situation has gutted their revenue by an estimated $210 billion in 2021, according to a study by AlixPartners, and auto manufacturing could suffer through 2023.

The shortage forced carmakers to halt production, including Ford Motor, General Motors, Toyota, Nissan, Subaru and Stellantis (formerly Fiat Chrysler). Some carmakers have shipped autos without accessories that need chips, leaving customers without touchscreens in their new cars. Tesla got credit for weathering the storm better than most, but it’s still suffering from chip constraints.

Gaming consoles also have been hit hard. The chip shortage meant fitful availability and poachers jacking up prices for the Sony PS5 and Microsoft Xbox Series X. The Nintendo Switch and Valve’s Steam Deck arrived late, too.

Even Apple has suffered, despite being led by supply chain guru Tim Cook and having the clout to place massive orders years in advance. The iPhone 12 launch was weeks late, and chip shortages continued to hit Apple through 2021.

To cope with the problem, PC maker Framework has had to make “risk buys” by purchasing extra inventory of components well ahead of time, said CEO Nirav Patel, though it’s weathered the storm so far. “It’s definitely a long-term, extended challenge for everyone,” he said.

To secure capacity for future products, “fabless” chip designers like Nvidia, AMD and Qualcomm pay billions of dollars to chip manufacturers. Intel expects such prepayments as well through its new foundry business. Smartphone chip designer Qualcomm expects sufficient capacity midway through 2022 thanks to such capacity planning. “Our supply has increased significantly,” CEO Cristiano Amon told The Verge in a January interview. “The chip shortage is not over yet, but things are getting much better as we go to the first half of 2022.”

What are chipmakers doing to ramp up manufacturing?

Semiconductor manufacturers are working harder to squeeze every last wafer through their fabs. But there’s not much they can do about the immediate shortage.

It takes years to build a fab. Intel just started building two new facilities, Fab 52 and 62 in Arizona, at a cost of $20 billion. But they won’t begin mass manufacturing until the second half of 2024, said Keyvan Esfarjani, leader of Intel’s manufacturing and supply chain.

But today’s shortage is accelerating tomorrow’s investment. Chipmakers like Samsung, GlobalFoundries, Intel and TSMC see demand for semiconductors surging as digital technology spreads far beyond computers and smartphones.

“We see the digitization of everything,” Gelsinger said.

Gelsinger has urged automakers to shift their processors to newer manufacturing technology that, thanks to miniaturization, can squeeze more chips out of a single 300mm-wide silicon wafer. That’s not an easy change, though, given that much of the auto industry selects and validates components that are used for years. It could help Intel’s effort to become a foundry that builds others’ chips, though, not just its own products.

OK, how expensive is this investment?

Hoo boy. Chipmakers’ coming capital investments are extraordinary. Intel trumpeted $23.5 billion in spending this year in the US, followed by plans for two “megafabs” in coming years totaling $200 billion. “These are big sites — something like over 1,000 acres,” each with room to fit eight fabs, Esfarjani said.

TSMC’s investments include a new fab in Arizona and a new fab partnership in Japan with Sony. Samsung expects to spend $145 billion through 2030.

“Five years ago, people said we were boring,” Su said. “The world has really realized this is now an essential part of what people do.”

In November, Samsung announced that one of its investments is a $17 billion fab in Taylor, Texas.

The shortage also gave new power to lesser-known chipmakers still building chips with earlier-generation “legacy node” manufacturing technology. That includes ST Microelectronics, Onsemi, Microchip, NXP Semiconductors and Infineon. GlobalFoundries, the manufacturing division AMD spun off in 2018, held its initial public offering despite a lack of profitability and bowing out of the race to keep up with the three leading-edge chipmakers: Intel, Samsung and TSMC.

GlobalFoundries is investing $1 billion to increase its current fab capacity in New York and add another fab there. It’s also building a fab in Singapore and expanding one in Germany.

Companies that build semiconductor manufacturing tools are raking in the money. Globally, spending on chip equipment will rise 10% in 2022 to a record high of $98 billion, the third year of growth in a row, the trade group Semi said in January. South Korea is the biggest spender, followed by Taiwan and China, collectively accounting for an expected 73% of spending this year. Korean spending should increase 14% in 2022, but spending in the US and China likely will decrease, the group said.

ASML, the Dutch company that’s the premier maker of the lithography equipment critical to shrinking chip electronics, has seen orders surge. It’s already received its first order for a next-gen machine — likely from Intel, which said it’s first in line. The truck-sized equipment inscribes circuitry with extremely short wavelength extreme ultraviolet, or EUV, light and focuses it more precisely with high numeric aperture (high NA) optics. Those devices will cost chipmakers an average of $340 million each.

What are the political repercussions?

US politicians, attuned to economic ebbs and flows, don’t like it when consumers can’t consume. The Biden administration has been trying to respond federally to the supply chain problems. It prodded companies to be more transparent about their needs and supplies, called on Congress to create the Critical Supply Chain Resiliency Program and started working to foster more US independence from international suppliers.

And there’s been more than a little freaking out that the US military is so reliant on overseas companies. As a 250-page White House report put it in June: “Semiconductors … are fundamental to the operation of virtually every military system, including communications and navigations systems and complex weapons systems such as those found in the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. They are key to the ‘must-win’ technologies of the future, including artificial intelligence and 5G, which will be essential to achieving the goal of a ‘dynamic, inclusive and innovative national economy’ identified as a critical American advantage in the March 2021 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance. In addition, the development of advanced autonomous systems, cybersecurity, space and hypersonics, and directed energy is also dependent on semiconductor technologies.”

The push also dovetails with the Biden administration’s Made in America effort to increase government spending on US-made products and boost US manufacturing more broadly.

The term that encapsulates the desired outcome? Supply chain resiliency. That means flagging problems sooner, making the government and private sector more adaptable, and building supply buffers of inventory that cushion supply chain shocks. Overall, that would reduce the likelihood and severity of supply chain surprises.

“The industry is begging for derisking,” said Capgemini analyst Darshan Naik.

What does that mean for chipmakers specifically?

In short, money. Congress authorized $52 billion in subsidies for chipmakers in the CHIPS for America Act, but Congress has yet to actually appropriate the funds. The Senate in June passed the United States Innovation and Competition Act, or USICA, to allocate funds. In February, the House followed suit, passing its America Competes Act with $52 billion in funding.

Even if the bill is signed into law Intel can’t pocket the full $52 billion. But $10 billion of that is earmarked for fab projects, with a cap of $3 billion per project and Intel a likely beneficiary. That 30% discount is comparable to what chipmakers in South Korea and Taiwan get, Gelsinger said.

Some of the tech industry’s biggest names agree. In a Dec. 1 letter, the CEOs of Apple, Google parent Alphabet, Verizon, Dell, HP, Toyota America, Ford, GM, Stellantis and IBM joined chip leaders from Intel, AMD, TSMC, Samsung, GlobalFoundries and others to urge Congress to pass funding for the CHIPS Act.

“Semiconductors are essential to virtually all sectors of the economy — including aerospace, automobiles, communications, clean energy, information technology, and medical devices,” the execs said. “Demand for these critical components has outstripped supply, creating a global chip shortage and resulting in lost growth and jobs in the economy. The shortage has exposed vulnerabilities in the semiconductor supply chain and highlighted the need for increased domestic manufacturing capacity.”

Intel will build its Ohio megafab regardless of government funding, but the funding will make the project bigger and accelerate Intel’s expansion, Esfarjani said. The company plans to settle on its European megafab site in coming months, he added.

Gelsinger has argued that only companies headquartered in the United States — which is to say Intel and not Samsung or TSMC — should benefit from US subsidies. “Foreign chipmakers vying for US subsidies will keep their valuable intellectual property on their own shores, ensuring that the most lucrative and cutting-edge manufacturing stays there,” Gelsinger said in a June op-ed.

But even fabs owned by overseas companies can help anchor electronics manufacturing in the US, develop trained workers, and generate economic activity and taxes. “In addition to our partners in Texas, we are grateful to the Biden Administration for creating an environment that supports companies like Samsung as we work to expand leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing in the US,” said Kinam Kim, the CEO of Samsung Electronics Device Solutions Division, in a statement.

Is this happening just in the US?

Nope. The European Union also wants a bigger piece of the processor production pie.

Its push for technological sovereignty led the European Union to propose an 11 billion euro European Chips act that could be pooled with 4 billion euros in other spending and 30 billion in earlier commitments to help chip manufacturing in Europe. The goal is to increase Europe’s share of chip manufacturing from 9% today to 20%.

“The pandemic has also painfully exposed the vulnerability of chips supply chains. … We have seen that whole production lines came to a standstill, for example with cars,” said European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in February. The European Chips Act’s goals are to increase resilience that will insulate European manufacturing from supply chain disruptions and to “to make Europe an industrial leader in this very strategic market.”

Here, too, Intel is a fan. It plans to build another $100 billion megafab in Europe.

Can you really move the whole electronics industry to the US?

No way. The electronics industry is vastly larger than just making chips, including upstream supplies like wafers and manufacturing equipment and downstream activities like packaging, testing and assembly, most of it in Asia. “There’s a lot of other aspects of the supply chain, and I believe those need to be more balanced as well,” Gelsinger said.

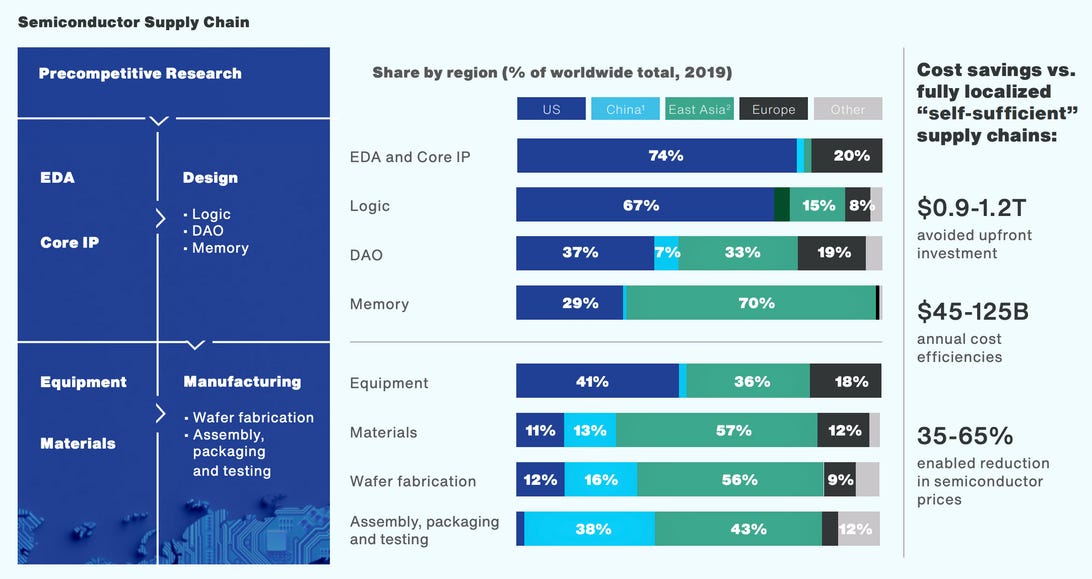

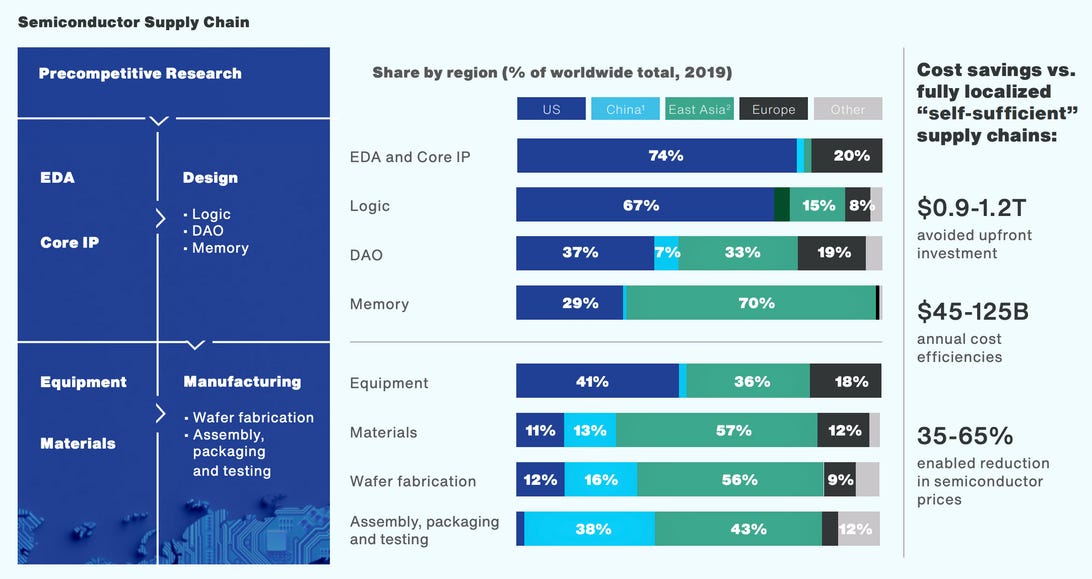

Here’s where $52 billion starts looking like a small expenditure. The Boston Consulting Group expects it would take $900 billion to $1.23 trillion in spending to create self-sufficient semiconductor supply chains worldwide. For just the US, it’s $350 billion to $420 billion. And that cost runs contrary to the capitalistic impulse to reward the least expensive suppliers.

“It’ll definitely create supply chain inefficiencies,” BCG analyst Matt Langione said. “Costs will go up. But there should be more redundancy in the system.”

Nearshoring, which would move manufacturing operations nearer to the US but not all the way, is another possibility, particularly for assembly, testing and other work not quite as high-tech as the chipmaking itself. “Mexico could be a strong option,” CapGemini’s Naik said.

Different regions develop specialties in semiconductor manufacturing around the world, and reproducing that expertise locally would cost $900 billion to $1.2 trillion, says a Boston Consulting Group study.

Boston Consulting GroupTSMC founder and former CEO Morris Chang is skeptical. “It’s not going to be possible to turn back the clock,” Chang said in October. “If you want to reestablish a complete semiconductor supply chain in the United States, you will not find it to be a possible task.”

Chip players naturally clump into “highly concentrated clusters,” consulting firm Deloitte said in a December report. Spreading that work geographically will help supply chain woes, but it’s not easy. “Clusters create strong pools of talent and skills. Prior attempts to build more geographically distributed manufacturing capacity (such as Silicon Glen in the United Kingdom in the late 1970s) came to naught,” Deloitte concluded.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology believes investments need to happen at the research level, not just with chipmakers. “The hollowing out of semiconductor manufacturing in the US is compromising our ability to innovate in this space and puts at risk our command of the next technological revolution. To ensure long-term leadership, leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing in the US must be prioritized and universities activities have to get closer to it,” MIT said in a January report. It called for upgrades from 1990s-era technology that tiles chips onto silicon wafers 150mm in diameter to equipment with 200mm wafers that are newer if not cutting edge.

Who loses from splitting electronics supply chains?

Rebalancing global supply chains doesn’t sound so great for companies that don’t benefit, like Chinese phone and network equipment maker Huawei, a giant with $71 billion in revenue for the first three quarters of 2021. The Trump administration believed its network equipment posed a national security threat, and the Biden administration agrees, so sales of Huawei products continue to be blocked. Raising barriers against overseas companies and promoting US ones could lead China or others to take the same stance against US companies, said Andy Purdy, chief security officer of Huawei USA.

“There are some major unintended consequences [of trade barriers] that are really going to hurt the US in the long term,” Purdy said. “If the American semiconductor industry is not allowed to sell to Huawei or Chinese companies, that’s going to undo a lot of the good things the Biden administration is trying to do.”

Indeed, Huawei has switched away from some US-made chips.

But even Andrew Feldman, CEO of AI chip and computer maker Cerebras, thinks there’s a risk of relying too much on Samsung and TSMC — his company’s chip manufacturer.

“What a bad idea it is for so much of the American economy to rely on a fab you can swim to from China or that you can throw a stone to from the DMZ in Korea,” Feldman said.