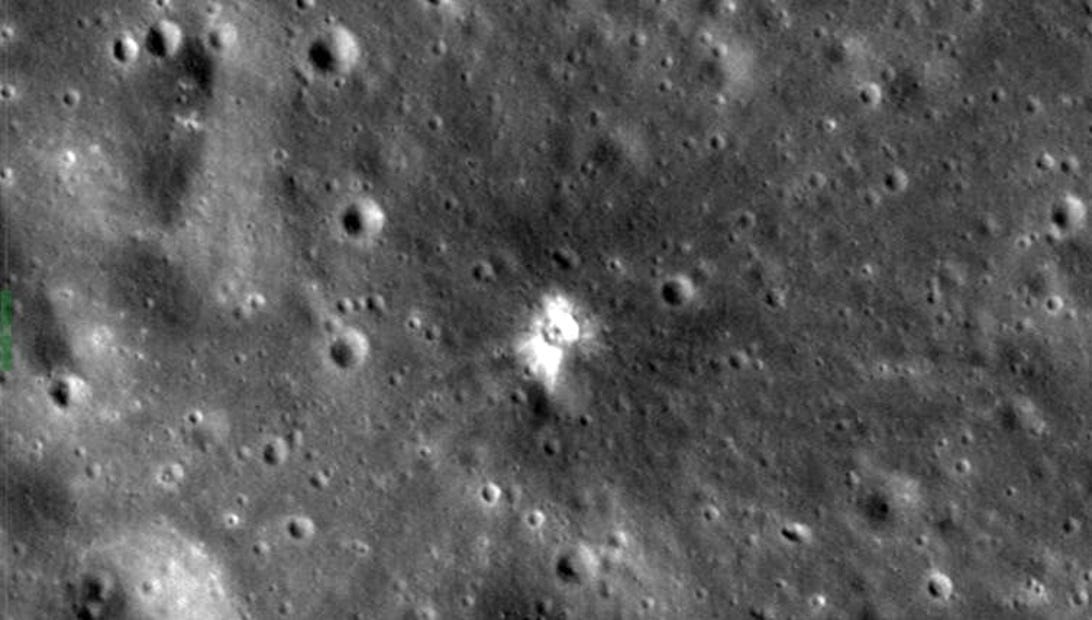

A natural impact on the moon created this crater in 2013. It’s about to get another.

NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/Arizona State UniversityThe strange story of a big hunk of space junk that’s on a collision course with the moon comes to an explosive end Friday, and astronomers are eager to view the fallout.

An old rocket booster once thought to be the upper stage of a SpaceX Falcon 9, but now believed to be from the Chinese Chang’e 5-T1 mission (although China denies this), will slam into the moon’s far side at over 5,000 miles per hour.

Bill Gray, an amateur astronomer and software developer in Maine, first noticed the terminal trajectory. His software picked up the impact in an orbital model and Gray worked with observatories around the world to gather additional data and increase his confidence in the prediction.

Gray believes he misidentified the booster as a Falcon 9 years ago. He and other researchers have since confirmed it to be the Chinese rocket part instead.

“I am astounded that we can tell the difference between the two rocket body options — SpaceX versus Chinese — and confirm which one will impact the moon with the data we have,” Adam Battle, a planetary science graduate student at the University of Arizona said in a statement in February. “The differences we see are primarily due to type of paint used by SpaceX and the Chinese.”

In a blog post, Gray wrote that “with all the data, we’ve got a certain impact at March 4 12:25:58 Universal Time (4:25 a.m. PT).” Jonathan McDowell, a leading watcher of orbit and everything near Earth in space, confirmed the prediction.

So the rocket about to hit the Moon, it turns out, is not the one we thought it was. This (an honest mistake) just emphasizes the problem with lack of proper tracking of these deep space objects. https://t.co/JXKpUmEC2X

— Jonathan McDowell (@planet4589) February 13, 2022

The rocket will crash into the lunar surface in a crater named Hertzsprung that’s a little larger than the state of Iowa. The location is remote enough that the impact doesn’t pose any threat to the Apollo mission or other space program landing sites.

“The upcoming rocket impact will provide a fortuitous experiment that could reveal a lot about how natural collisions pummel and scour planetary surfaces,” University of Colorado Boulder planetary scientist Paul Hayne writes for The Conversation. “A deeper understanding of impact physics will go a long way in helping researchers interpret the barren landscape of the Moon and also the effects impacts have on Earth and other planets.”

Hayne expects the impact will obliterate the rocket instantly and create a white flash that could be visible if any spacecraft were in place with a vantage point. That doesn’t seem likely, however. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter won’t be in a position to start taking photos of the impact site until mid-March.

“It will be the moon’s newest archaeological site,” writes space archaeologist Alice Gorman. “We’ll learn something about the geology of the location from the color differences and distribution of the ejected material. It’s an opportunity to learn more about the moon’s mysterious far side.”

Besides adding a new feature to the dark side of the moon, there’s some concern it could also introduce tiny hitchhikers to our natural satellite.

“So I’m not bothered by one more crater being made on the moon,” David Rothery, professor of planetary geosciences at the UK’s Open University, wrote in The Conversation. “It already has something like half a billion craters that are 10 meters or more in diameter. What we should worry about is contaminating the moon with living microbes, or molecules that could in the future be mistaken as evidence of former life on the moon.”

The European Space Agency issued a statement last month raising its concern that not enough is being done to track space junk, as NASA and others hope to establish a permanent presence on the moon.

“The upcoming lunar impact illustrates well the need for a comprehensive regulatory regime in space, not only for the economically crucial orbits around Earth but also applying to the moon,” said Holger Krag, head of ESA’s space safety program.

This won’t be the first time a spacecraft has slammed into the moon, although Gray thinks it might be the first time it’s happening unintentionally. As recently as 2009, NASA slammed its Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (Lcross) into the surface in a search for water (it found some).

“In essence, this is a ‘free’ Lcross,” Gray says. “Except we probably won’t see the impact.”