Ever wondered what a bacteria sonata would be like?

Christoph Burgstedt/GettyIf you give a bacterium a graphene drum, you’ll be rewarded with a sick beat. Yes, you read that correctly.

Scientists recorded the remarkable soundtrack of bacteria by fostering just the right conditions for a microorganism concert. They describe the resulting sound in a paper published Monday in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

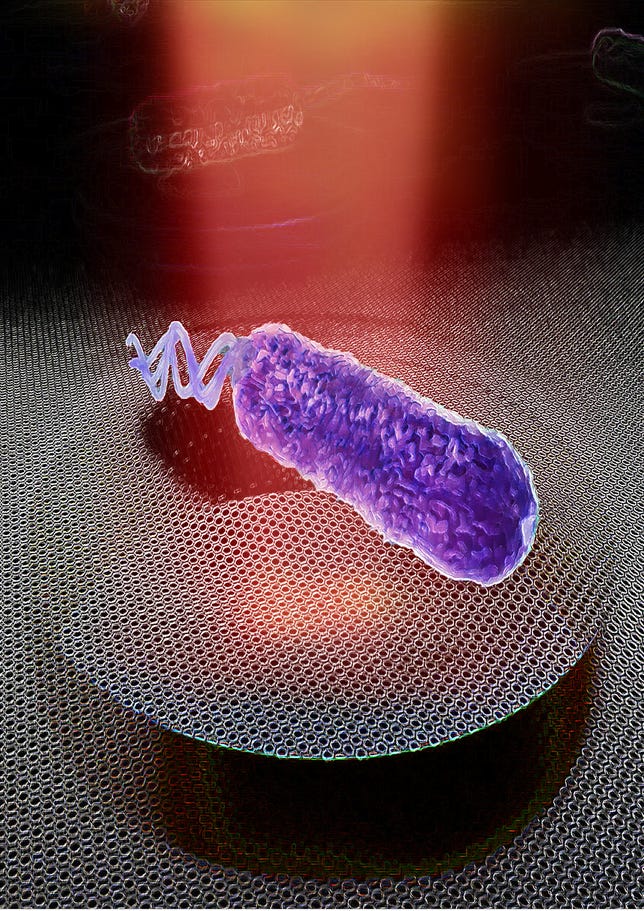

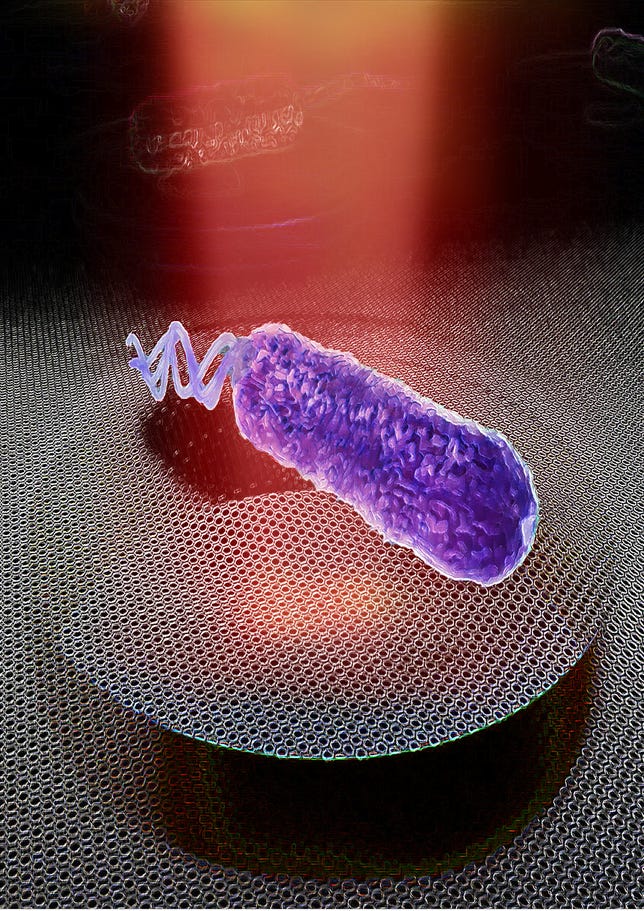

They simply placed these one-celled beings on a material called graphene, sat back and waited to see what would happen. Graphene is a unique variation on carbon that’s sometimes referred to as a “wonder material,” because it’s super sensitive to stimulation yet only one atom thick.

“What we saw was striking,” Cees Dekker, a researcher at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands and co-author of the study said in a statement. “We could hear the sound of a single bacterium.”

And you can tune in, too. Here’s a sample of Escherichia coli’s newest hit single.

OK, it’s no Hans Zimmer or Radiohead — and in fact, sounds pretty much like a wind tunnel — but think about what you just listened to. This is the sound of one of the tiniest living things in the universe.

More specifically, what you’re hearing is the sound of bacteria tails, or flagella, interacting with the graphene drum and producing back-and-forth movements called oscillations. Such oscillations generate vibrations on the material’s surface, and the scientists later converted all of that into noise you can hear.

“To understand how tiny these flagellar beats on graphene are, it’s worth saying that they are at least 10 billion times smaller than a boxer’s punch when reaching a punch bag,” said Farbod Alijani, a researcher at the Delft University of Technology and co-author of the study. “Yet, these nanoscale beats can be converted to soundtracks and listened to — and how cool is that.”

An artist’s impression of a graphene drum detecting nanomotion of a single bacterium.

Irek Roslon, TU DelftBut beyond the sheer awesomeness of this discovery, the team’s finding could also have an important medical application. Listening to the sounds of bacteria could help us understand the effectiveness of antibiotics — aka bacteria killers — because, well, you know what would happen to a bacterium’s sonata if an antibiotic obliterates the microbe?

It would stop.

During their experimentation, the study team clearly saw that if bacteria were resistant to an antibiotic, their beats would continue. If bacteria were susceptible to the medication, the song slowed, and slowed, until it was completely gone.

“This would be an invaluable tool in the fight against antibiotic resistance, an ever-increasing threat to human health around the world,” said Peter Steeneken, a researcher at Delft University of Technology and another co-author of the study.

“For the future, Steenken added, “we aim at optimizing our single-cell graphene antibiotic sensitivity platform and validating it against a variety of pathogenic samples so that eventually, it can be used as an effective diagnostic toolkit for fast detection of antibiotic resistance in clinical practice.”

Until then, we ought to add the white-noise-like bacteria music to a playlist of calming sleep soundscapes.