Customs agents at Detroit Metropolitan Airport who were checking the baggage of a passenger traveling from the Philippines found something just around half an inch in size that piqued their interest.

The objects in question — the larvae and pupae of an unidentifiable insect — were inside seed pods that the passenger said were intended for medicinal tea. Later, scientific tests showed that the agents had homed in on a potentially grave threat to the nation’s agriculture and natural habitats.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection announced last week that the pupae had hatched a species of moth whose last recorded sighting by scientists occurred in 1912 in Sri Lanka. Experts confirmed that such nonnative insects had the potential to defoliate forests and feast on or contaminate crops.

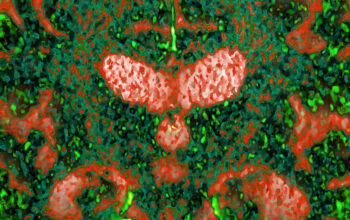

The moths, whose black-and-gold-dotted wings resemble a cloudy predawn sky, were discovered in September and looked to be a member of the moth family Pyralidae, the customs officials said. To determine their exact species, the authorities sent the specimens to M. Alma Solis, a moth specialist at the Agriculture Department.

Dr. Solis said in a telephone interview that she received a FedEx package on April 19 containing a box with one adult moth and vials with caterpillars and pupae.

“I did my Ph.D. on this subfamily; I’m a world expert,” she said. “I can identify something to subfamily almost immediately. Then it’s a matter of knowing the literature.”

Dr. Solis said she is one of four moth research specialists working full time for the U.S. government who are capable of identifying rare or little-known species that arrive at the nation’s borders.

In addition to these specialists, there are also agricultural inspectors at ports who are able to recognize potential threats. In this case, Dr. Solis said she worked with Tyler Fox, a Detroit-based agriculture specialist with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, who knew that she was an expert in this particular type of moth.

“He’s a pretty incredible entomologist,” Dr. Solis said. Mr. Fox, who did not respond to a request for comment, and his colleagues must have wide-ranging knowledge “of just about every organism you can think of,” she said.

“They’re looking at species coming in from all over the world, of many different organisms, and they’re called upon to send it to the right specialist,” Dr. Solis said. “It’s just amazing what they find, in my opinion.”

It was unlikely that the moths were smuggled into the country, according to two experts: Jason Dombroskie, a lepidopterist at the Insect Diagnostic Lab at Cornell, who specializes in identifying moth species; and David Moskowitz, an entomologist, environmental consultant and co-founder of National Moth Week, an annual event that encourages people to observe moths in backyards and parks. Mr. Dombroskie and Mr. Moskowitz said that the species was too obscure to possess the medicinal or aesthetic value that motivates smugglers.

But both experts emphasized the danger that the species might have posed, given the destructiveness of other nonnative insects.

For example, the spongy moth (until recently known as the gypsy moth) has become a tree-devouring pest responsible for hundreds of millions of dollars in damage and mitigation efforts annually, according to the Entomological Society of America.

And scientists have feared that the emerald ash borer, an Asian beetle, has the potential to kill 99 percent of the nation’s ash trees.

“The emerald ash borer originated in Detroit,” Mr. Dombroskie said. “If we’d had an agricultural inspector that identified that early on, we could have prevented all that.

“Would this moth have become the next multibillion-dollar pest?” he asked, referring to the species found by the customs agents. “Probably not — but it’s possible.”

The identification of such tiny but potentially devastating larvae was “improbable,” Mr. Dombroskie said.

“There’s only so much you can know,” he added. “A botanist might not have made this discovery, or a mycologist,” someone who works with fungi like molds and mushrooms.

Mr. Moskowitz said the episode illustrated the importance of training in animal taxonomy for customs agents.

“Identifying a moth that hadn’t been found in more than a century took great expertise,” he wrote in an email. “Without that, we lose the ability to know what is around us, how we might be able to protect and conserve species at risk and against invaders.”

With the global supply chain connecting countries and travelers shifting between world capitals, Mr. Moskowitz continued, protecting the country from invasive pests “is truly a herculean task.”